Ward Janssen: new emotional technology boundaries

Describe your path to what you’re doing now.

I started as head of digital culture of the Cinekid Festival and foundation in April 2017. At Cinekid I am the curator of the festivals’ MediaLab, a big exhibition about digital culture with artworks and installations, workshops and games. I also work on other projects for the organization, this year mainly the new and improved Cinekid Media Awards.

Before Cinekid I was curator at MOTI, Museum of the Image, that sadly merged into a new museum with a focus on local heritage. Clearly not my cup of tea.

At MOTI Museum I worked on many exhibitions, projects, publications and commissions for artists about visual culture and specifically digital culture in our daily lives, the arts, design, and beyond that. I acquired a lot of digital artworks for the museum collection, specifically in collaboration with Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, we acquired 17 digital artworks by international artists in 2016. Before my work at the museum I programmed for film festivals, curated and produced exhibitions amongst others.

Have you always been a curator? or when did you have that “Aha!” moment about what you wanted to do?

I haven’t, actually. I started way back in fashion as a photographer. Around that time I also started writing for a lot of artists. I’ve always been collecting images religiously, trying to sort out what they meant or how they were connected. I started programming for a film festival about eight years ago. After that came exhibitions, more film programmes, art projects and a focus on art/design/film cross overs. Then a museum job as a curator. So it sort of evolved naturally, over time.

Where lies the seed of your interest in digital culture/media?

As soon as I started programming film it was always with an emphasis on experimental projects, and many of those turned out to be digital. This was when fashion film was starting and experiments on the web in publishing non conventional projects were new. I had a deep love for messy computer stuff, mixed in with the more conventional works. I started collecting digital projects to remember them way before I got to curating them, I guess. Looking back, as obsessed as I was with the internet from early on, it sort of makes sense that I do what I do now. But there wasn’t a plan or something I meticulously mapped out. It was all very coincidental.

What is digital culture for you now and how vibrant is the Dutch / international scene?

The Dutch scene is terrific because it was so well funded right around the time the digital art scene started in the nineties, so we have a good history, as short as that history is. But that is also very art oriented (obviously, hence the funding) even if the topics addressed are quite aggressive in their stance towards the global digitalization of our world; the web becoming mainstream and growing deeper and deeper into what it is now. Ever changing naturally, sometimes horribly. I like the digital art scene but I love the digital cesspool of the messier internet. So where the two meet I’m happiest. And of course this is global. I do like the French especially, as they have their own weird integrity that is so unconventional by any (digital) art standard, traditional in artistic approach but so dirty in result. The Netherlands are in my opinion a very good in between space to get at everything and anything: the political scene in Berlin, the high brow scene in New York, the tacky-but-good scene in L.A. And we have a good old art scene and a good feisty academic scene in Amsterdam and Rotterdam that is at it’s core hesitant towards tech optimism, which helps a lot to keep things grounded, in digital art and in appreciation of digital culture in general.

Since one year you are curator digital media for Cinekid, a children’s festival for film, television and digital culture. Is curating for children different then for adults?

Yes, of course. Very much actually. But perhaps not in the way you’d think. I’m curating a lot of the same artists but I just have to explain their work differently. The impact has to be very direct, emotional, poetic. That means there is no place for irony, which is probably very healthy for the kids that see the exhibition. And I must say I loved and now sometimes miss a bit the appreciation of very complicated, nuanced artworks and artists. There is little room for the intellectual digital activist crowd, but lots of possibility to focus on poetics and absurdity. So it levels out nicely.

The focus is on poetry and qualitative presentation. And let’s be honest, this is something that is lacking in many presentations of digital culture or digital art in conventional exhibitions anyway. So we get to focus on bravoure and quality nonetheless and perfecting what needed to be better anyway.

You programmed the digital culture section of the Cinekid Festival. Which has two sections MediaLab and a conference for professionals. Can you walk us through the MediaLab program?

These two parts of the festival are very different, the conference is not for the children, of course.

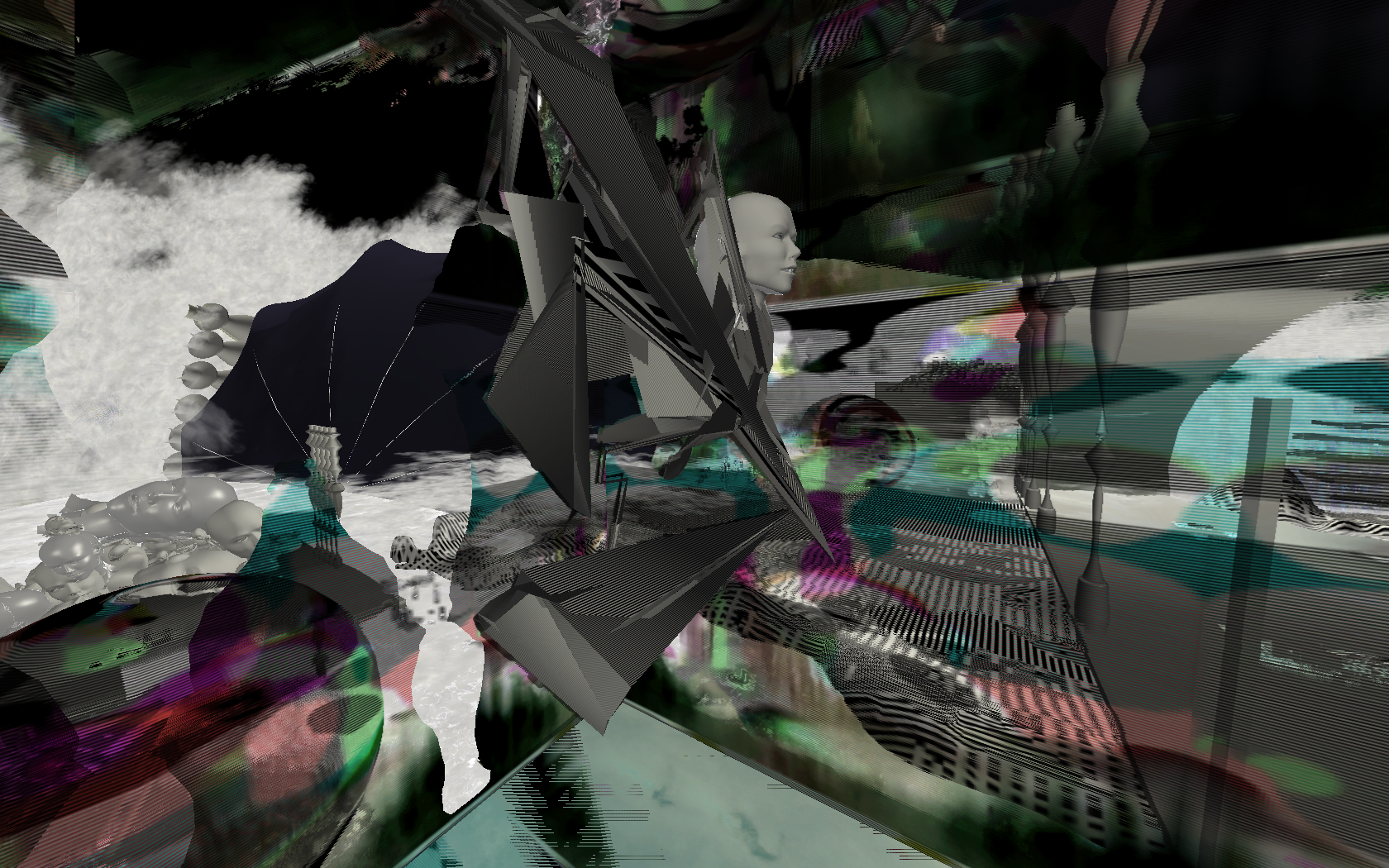

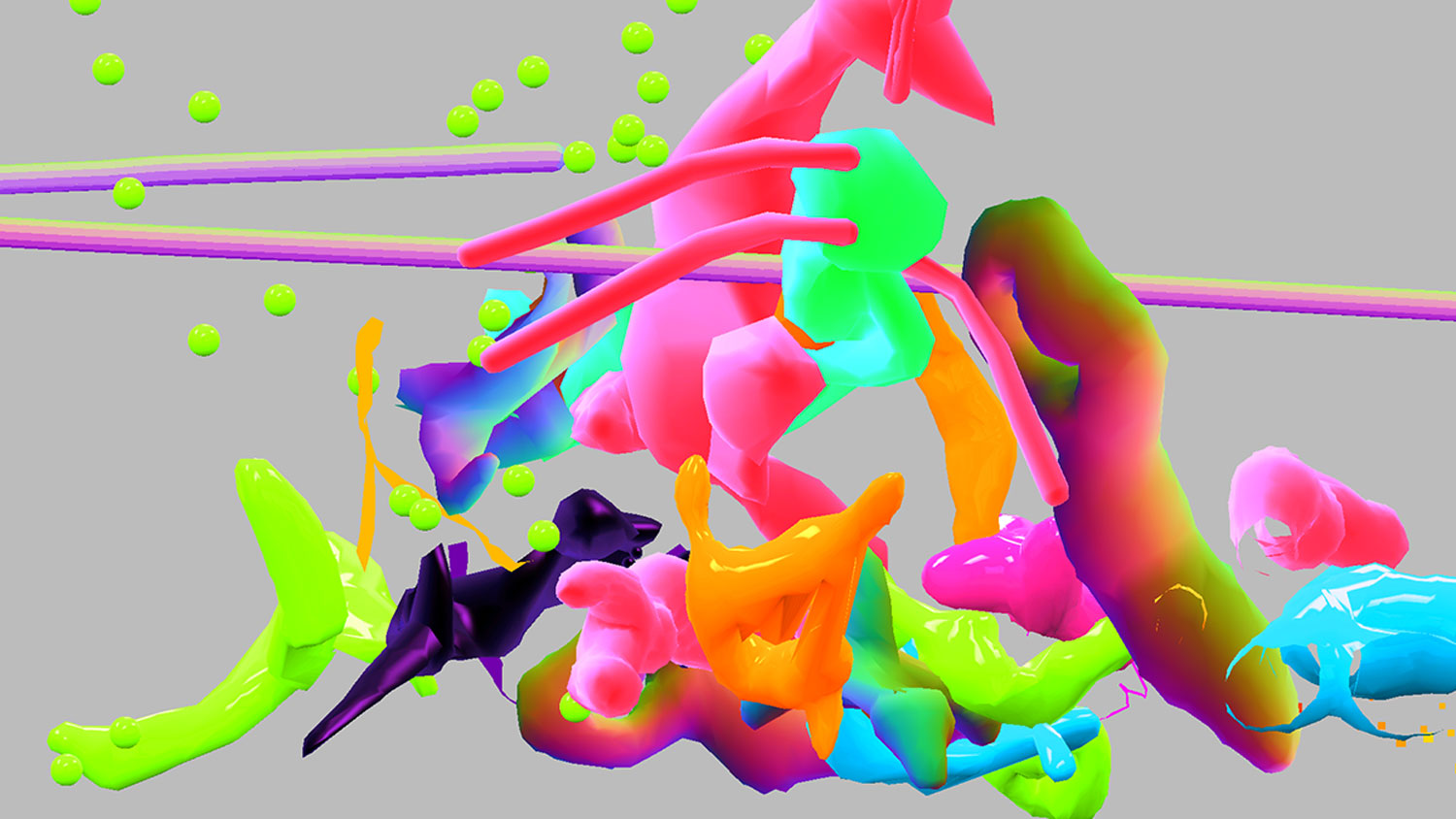

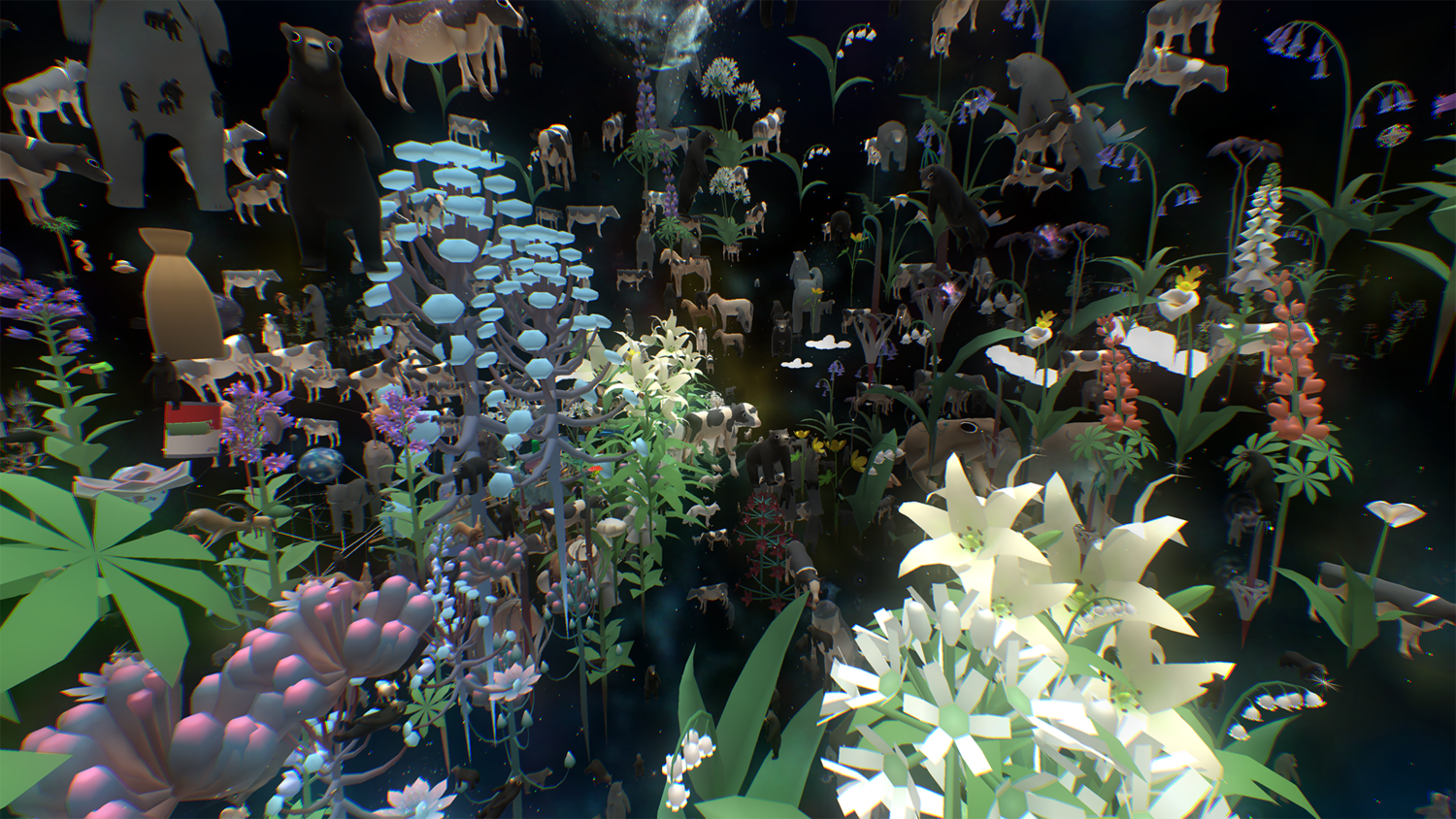

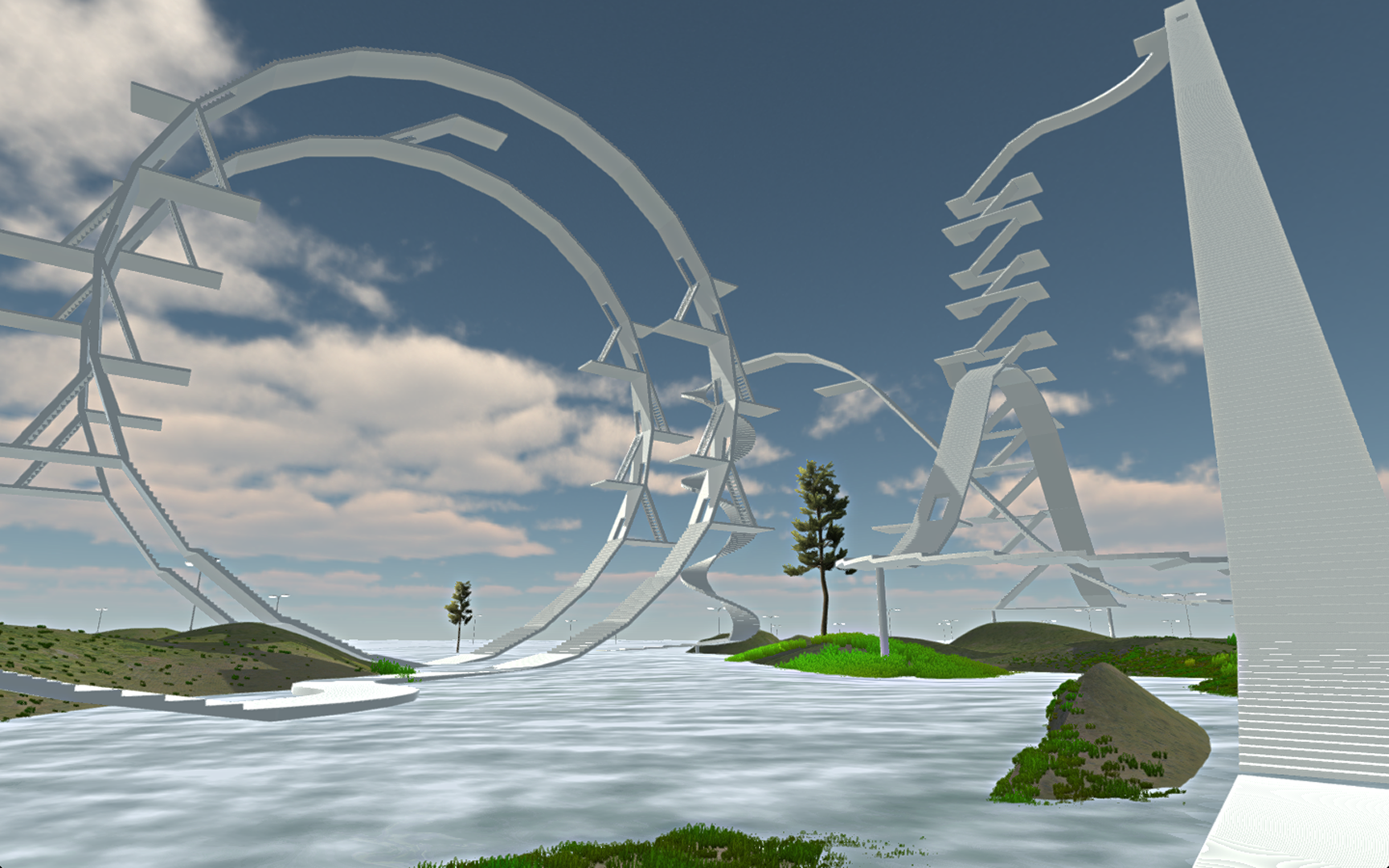

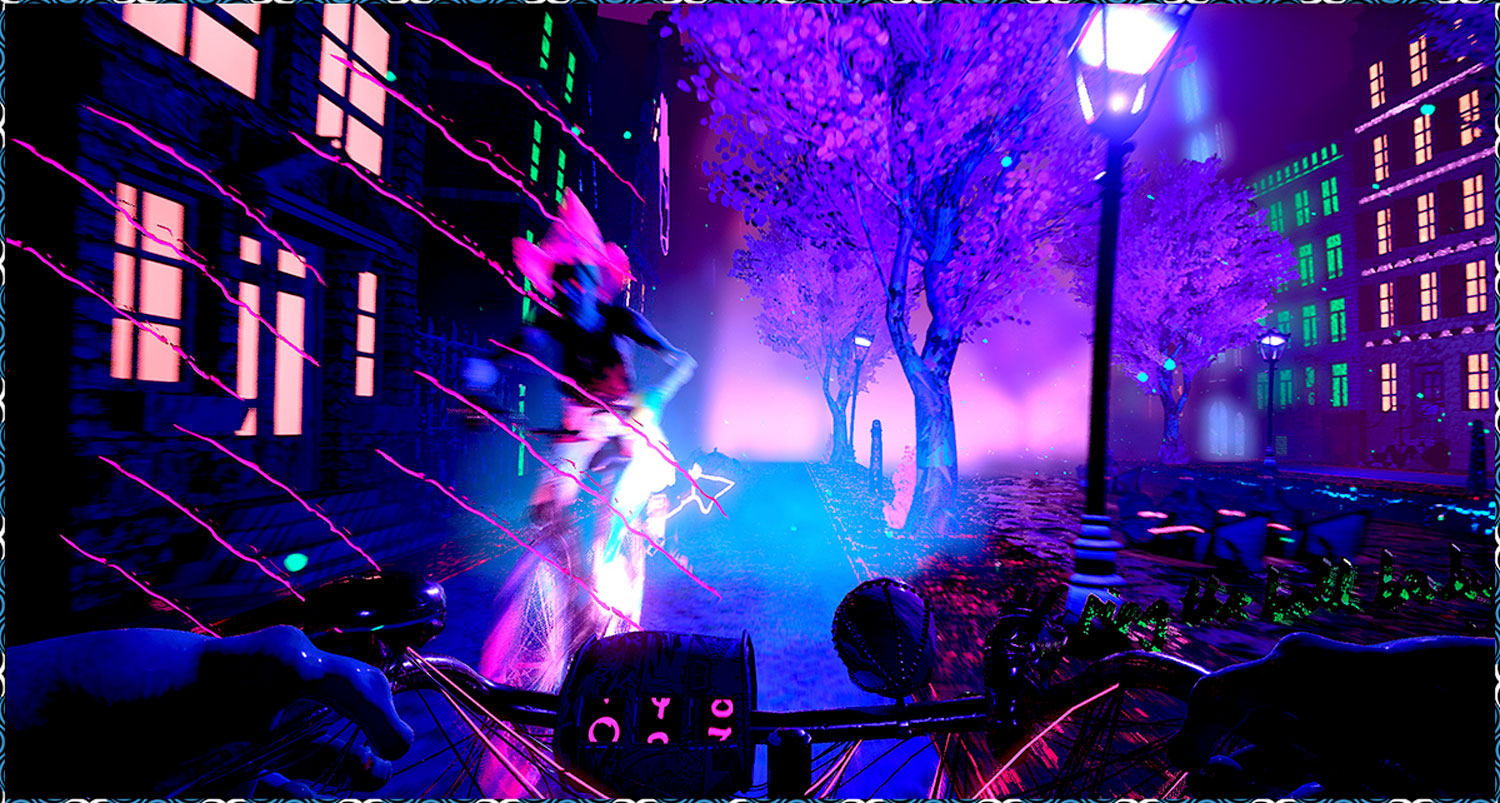

In the MediaLab I’m excited about some new and very challenging V.R. projects by Geoffrey Lillemon & Anita Fontaine (for the Dept of New Realities, part of Wieden Kennedy) and youngsters Teyosh. I love that we show Rafael Rozendaals net art projects, to kids they are just crazy puzzles basically. My favorite piece is a combination of five artworks that are game environments of digital landscapes, that we combine in one big set up as a circular room. It shows works from Theo Triantafyllidis, Rosa Menkman, Kristin Lucas, The Rodina and David O’Reilly. David’s work I programmed years ago as well for film festivals and he is terrific.

On an educational level: we do many workshops of course about technology and storytelling (horrible marketing term), but also a course in Emoji design for instance. But when I started this job I discussed at length with my new director Floor van Spaendonck that I thought the best educational experience was a set up where a child of any age gets to focus on watching, analyzing contemporary beauty and poetics. I’m quite old fashioned that way. But the art is not, so it should work out.

The conference is very different, for professionals from all over the world, and focuses on new emotional technology boundaries. I love it, so far. We present keynotes from Nexus, Moniker and Regine Debatty, but also Geoffrey Lillemon and Anita Fontaine. And our head speaker is he amazing Monika Bielskyte. She is sort of an oracle on technology in artistic expression and the visualization of futuristic technological applications in film, Hollywood level. We end with a panel with her, me and Geoffrey & Anita.

The conference focus is on VR/AR/MR. Why this focus?

The afternoon part of the conference is actually about something else: emotional technology. We have a tech problem, in that we tend to focus on new models of immersivity. We try to see how we can make media intake more overwhelming. We want to discuss why this is the tech fashion of today and if this is in fact a good trend. Technology is by lieu of Silicon Valley so novelty driven we hardly have time to let new technologies like VR for instance, mature into a quality medium. The tech industry is in constant acceleration mode and we, users and artists and publishers alike, seem utterly submissive to what technology tells us is relevant, just because it is new.

For years we’ve been hearing plenty about VR and 360 as the new hot thing that will change our media society, make journalism more introspective for its’ audiences, make cinema obsolete.

I want to know why I’ve hardly ever seen any really good VR. And: do games need it? Do we really need for instance first person shooters to be this immersive? Is that not just traumatizing or at least distasteful? And where is that so often promised mature VR (or AR, or MR) artwork on a real level of international recognition? I see a lot of technology driven content and art and I usually just yawn, because it is boring. Or shrug, because it is not interesting quite yet.

With all these immersive technology opportunities (and promises) we should get better results. New technologies like VR are now often implemented as a new tech fancy metaphor of plain old seeing what is right in front of you. Or it is a deranged uncomfortable visual experience that is new but, well, not great? We either have to accept collectively that immersive technology can do better or we have a real problem of semantics, a collective and complete misunderstanding of what immersive means.

This is the main topic of debate. We have speakers that are dealing with this very problem in their work and that are bringing very personal ideas to the table in their productions. And their common denominator is perhaps that they are willing to see what the mess is, and are focussing on individual approaches to make immersivity in technology as a goal or at least an experience more interesting. Artistically.

What do you want your audience to take home after a visit to Cinekid?

These very different groups need very different conclusions in their head when they exit the MediaLab and the Cinekid Festival.

I want the kids to have memories for life. I remember museum exhibitions I saw as a child and that is character building, mind blowing and horizon broadening. This is a cliche, I know, but I remember visits to Centre Pompidou, orchestra performances of Beethoven, architecture pilgrimage trips to Le Corbusier in Marseille; all from before I was ten or twelve. And that is good stuff.

I want the parents (they pay the tickets) to think they just discovered digital MoMA in Amsterdam, and to realize it was very carefully presented as a full cultural and also fun loving (non artsy threatening?) experience for their kids.

The professionals at the festival are mostly film and television people, some art people. I want them to see quality that is better than it was in previous years and I have an international ambition for the festival. I’m competitive that way.

What's your ambition for the Medialab / Cinekid Conference in the next five years?

In curating the MediaLab the emphasis is on presenting new examples of digital poetics in large scale presentations. I want to combine that in the coming years with Internet found footage, so we don’t treat the digital realm just as an artists space, but as a populated global domain where constant changes in visibility of the digital world and individualism within it evolve through technology.

Other than that we will focus on getting more artworks commissioned internationally. We will do this first for Cinekid 2018 with partners La Gaité Lyrique (Paris), KiKK (Namurs) and WoeLab (Lomé) for the European project Capitaine Future. But we are also exporting projects in 2018. So right after the festival we will start focusing on international partnerships and funding new commissioned international projects mainly.

By the way: the iconic Dutch fashion journalist Aynouk Tan is announcing the three new commissions of Captain Future and the artists that will work on them on the MediaLab Night on October 25th. It’s a very good line up, let me tell you.

Who of the creatives you present we should absolutely follow?

Rick Silva, Kristin Lucas, David O’Reilly, Theo Triantafyllidis, Philip Schuette and Rosa Menkman. These names just because they have such a perfect and very personal idea of what digital material is and how it can be a new visual language to present, pin point, academically discuss through artworks. Of course I love the before mentioned Geoffrey Lillemon & Anita Fontaine for their craziness and attention to detail in crafting new ideas of realities in all technological possibilities, Luna Maurer and Roel Wouters from Moniker for diligence in and artistic integrity in using user content to make a collaborative concept lively and emotionally relevant in digital form, The Rodina for being bat shit crazy in a good way, Teyosh for being sweet and absurd in VR, Rafael Rozendaal for making digital and net art a Warhol arena, and so on.I love what Belgian artist Tom Galle is shaping as social media tongue in cheek activism. Jonas Lund is too clever, but he is solid. Roel Roscam Abbing and Dennis de Bel, often a duo, are exciting in how they bring lo fi tech to high brow activism/criticism against/of the ruling tech models of our economy. And so many more.

Cinekid Festival

21-27 October 2017

Amsterdam, NL

Tickets Pro

Tickets Kids